Why Crimea Is the Key to Peace in Ukraine

为什么克里米亚是乌克兰和平的关键

Opinion by RORY FINNIN 01/13/2023 04:30 AM EST The Politico

Rory Finnin is an associate professor of Ukrainian studies at the University of Cambridge. This article was adapted from his new book Blood of Others: Stalin’s Crimean Atrocity and the Poetics of Solidarity.

罗里·芬宁是剑桥大学乌克兰研究的副教授。本文改编自他的新书《他人之血:斯大林的克里米亚暴行与团结诗学》。

Peace is only possible if Ukraine keeps Crimea. Here’s why.

和平只有在乌克兰保留克里米亚的情况下才可能实现。原因如下。

The cost has been unbearable. But the deep sacrifices and hard-won battlefield successes of the people of Ukraine have already dealt an epic moral and strategic blow to the Kremlin. Now a Russian military defeat may be on the horizon, provided the West continues to give Ukraine the support it needs.

成本已经难以承受。但乌克兰人民深重的牺牲和来之不易的战场胜利,已经给克里姆林宫带来了史诗般的道德和战略打击。现在,只要西方继续给予乌克兰所需的支持,俄罗斯的军事失败可能就在眼前。

Whenever genuine peace talks begin, there’s little doubt that Crimea will feature high on the agenda. Ukraine’s Black Sea peninsula is the ground zero of Russia’s current war of aggression. Since its seizure by Vladimir Putin’s troops in 2014, Crimea has been flooded with weapons, disinformation and fear. Its residents have been cut off from the rest of Ukraine and the wider world.

每当真正的和平谈判开始时,克里米亚无疑将是议程上的重点。乌克兰的黑海半岛是俄罗斯当前侵略战争的零点。自从 2014 年弗拉基米尔·普京的军队占领克里米亚以来,这里被武器、虚假信息和恐惧所淹没。其居民已经与乌克兰其他地区以及更广阔的世界隔绝。

There had been a tendency in the West to look away from this Russian occupation of Crimea and shrug our shoulders. But with Ukrainian forces now staging a dogged counteroffensive and striking military targets inside Crimea, there seems to be precious little indifference today. Some pundits are calling on Kyiv to back down and dangle Crimea as a pawn in a future settlement with Russia. Amateur mediators like Elon Musk casually ponder surrendering the peninsula to Putin and calling it a day.

西方曾有一种倾向,对俄罗斯占领克里米亚视而不见,耸耸肩膀。但随着乌克兰军队现在发起顽强的反攻,并在克里米亚境内打击军事目标,今天似乎几乎没有人能够保持漠不关心。一些评论员呼吁基辅放弃抵抗,并将克里米亚作为未来与俄罗斯和解的筹码。业余调解者如埃隆·马斯克随意考虑将半岛交给普京,就此打住。

Such overtures are too quick to reward Russian aggression, which has razed entire cities and slaughtered thousands of Ukrainian civilians over the last year alone. And they are too slow to recognize that returning Crimea to Ukrainian control is not only a matter of moral and legal principle that would restore rights and freedoms to millions of people under the Kremlin’s occupation. It is also the only practical way any peace plan could succeed.

这些姿态对俄罗斯的侵略行为给予了过快的奖赏,仅在过去一年内,这种侵略就已经夷平了整座城市,屠杀了成千上万的乌克兰平民。同时,它们对于承认将克里米亚归还乌克兰控制的必要性反应过慢,这不仅是恢复数百万人在克里姆林宫占领下的权利和自由的道德和法律原则问题。这也是任何和平计划能够成功的唯一切实可行的方式。

The truth is Crimea has no natural physical connection to Russia. Crimea is an extension of the Ukrainian mainland, and as such, it has been deeply connected to and dependent on Ukraine’s resources and trade for centuries.

真相是克里米亚与俄罗斯没有自然的物理联系。克里米亚是乌克兰大陆的延伸,因此,几个世纪以来一直与乌克兰的资源和贸易有着深厚的联系和依赖。

Crimea’s historical experience of Russian and Soviet rule, meanwhile, has been one of persistent ethnic cleansing, violence and trauma. This helps explain why a majority of Crimea’s residents voted for Ukraine’s independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. It also helps explain why in 2013, prior to Russia’s invasion of the peninsula, a large majority of poll respondents in Crimea expressed the view that Crimea should be a part of Ukraine.

克里米亚历史上经历了俄罗斯和苏联的统治,这一过程中持续存在着种族清洗、暴力和创伤。这有助于解释为什么在 1991 年乌克兰从苏联独立时,克里米亚的大多数居民投票支持。这也有助于解释为什么在 2013 年,也就是俄罗斯入侵该半岛之前,克里米亚的大多数民意调查受访者表达了克里米亚应该成为乌克兰一部分的观点。

If the past teaches us anything, it is that Crimea suffers decline when separated from Ukraine, and that Crimea triggers conflict when occupied by Russia. Failing to understand this history is to sleepwalk into a future of more military escalation from the Kremlin.

如果过去的历史能教给我们什么,那就是克里米亚从乌克兰分离出去时会衰退,而被俄罗斯占领时会引发冲突。不理解这段历史就是在无意识地走向一个由克里姆林宫更多军事升级的未来。

In the spring of 2014, as Vladimir Putin’s “little green men” were invading Crimea, a Russian meme went viral on social media: KrymNash, or “Crimea Is Ours.” It was a classic imperialist message. Brash, insistent claims to conquered territory are what empires do to mask anxieties about their own political legitimacy. As Edward Said once remarked about empires and their colonies, “If you belong in a place, you do not have to keep saying and showing it.”

2014 年春,当弗拉基米尔·普京的“小绿人”入侵克里米亚时,一个俄罗斯的网络迷因在社交媒体上病毒式传播:KrymNash,或者说“克里米亚是我们的”。这是一个典型的帝国主义信息。帝国为了掩盖自身政治合法性的焦虑,总是大胆且坚持地宣称对征服地的所有权。正如爱德华·赛义德曾经关于帝国及其殖民地所说:“如果你属于一个地方,你就没有必要不停地说出来和展示。”

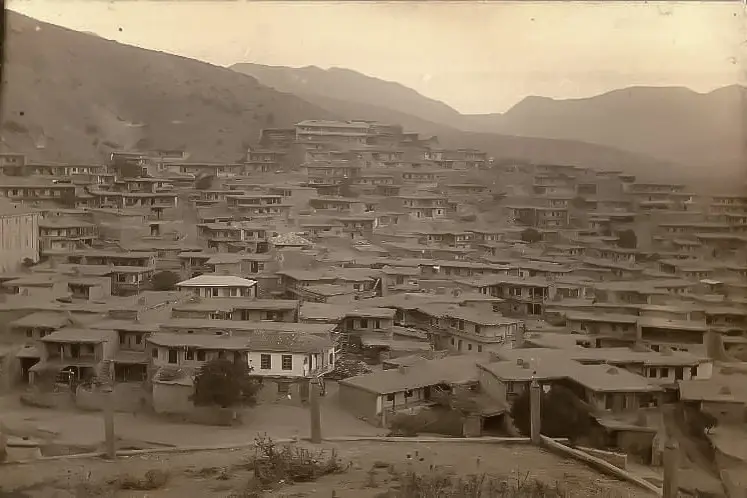

Russia is an expansionist land empire, and Crimea is one of its most prized colonies. The strategic port of Sevastopol is home to the Kremlin’s Black Sea fleet, while resort towns like Yalta on the mountainous southern coast offer Russian vacationers a rocky Riviera, an exotic playground of warm water beaches.

俄罗斯是一个扩张主义的陆地帝国,克里米亚是其最珍贵的殖民地之一。战略港口塞瓦斯托波尔是克里姆林宫黑海舰队的基地,而像雅尔塔这样的山区南海岸度假城镇为俄罗斯度假者提供了一个多岩石的里维埃拉,一个温暖水域海滩的异国情调游乐场。

But behind Crimea’s postcard image lie much deeper realities of demography, history and geography that Russia has anxiously tried to conceal and erase for a long time. One of them is the Crimea of the Crimean Tatars, who are recognized as an indigenous people of Ukraine.

但在克里米亚明信片般的形象背后,隐藏着人口、历史和地理等更深层的现实,俄罗斯长期以来一直焦虑地试图隐藏和抹去这些现实。其中之一就是克里米亚鞑靼人的克里米亚,他们被认定为乌克兰的土著民族。

For centuries Crimea was the dominion of the Crimean Tatar khanate, a Sunni Muslim Turkic-speaking state aligned with the Ottoman Empire. Only after invading Crimea four different times did Catherine II succeed in dismantling the khanate in 1783 and in absorbing its territory into a Russian Empire on the march.

几个世纪以来,克里米亚一直是克里米亚鞑靼汗国的领土,这是一个与奥斯曼帝国结盟的逊尼派穆斯林突厥语国家。只有在四次入侵克里米亚之后,凯瑟琳二世才在 1783 年成功地解散了汗国,并将其领土吞并进正在扩张的俄罗斯帝国。

But what Catherine acquired in 1783 was not what Putin grabbed in 2014. The territory of the Crimean Tatar khanate she annexed included both the Crimean peninsula and the adjacent steppeland of today’s southern Ukraine, which stretches along the shores of the Black Sea and Azov Sea. In fact, much of the frontline of today’s war follows the contours of what were once the northern reaches of the Crimean Tatar khanate.

但凯瑟琳在 1783 年获得的并不是普京在 2014 年夺取的。她所并吞的克里米亚鞑靼汗国领土包括了克里米亚半岛和今天乌克兰南部与黑海和亚速海相邻的草原地带。实际上,如今战争的前线很大程度上沿着曾经是克里米亚鞑靼汗国北部边界的轮廓。

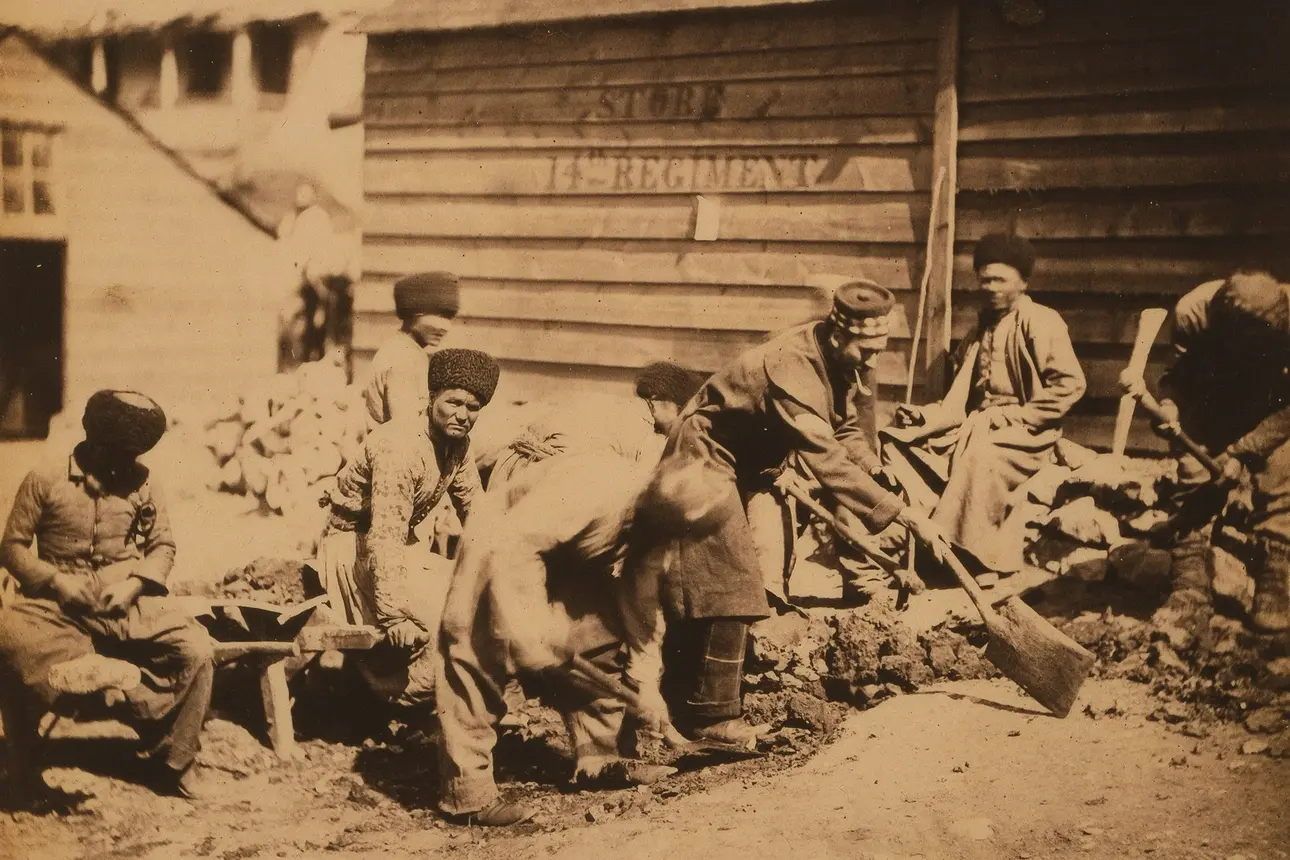

Decades after Catherine’s death, this Russian expansion came to a halt. In the mid-19th century, Crimea became the site of an imperial clash of the titans, with British, Ottoman and European allies facing off against Russia over control of the Black Sea region. The Crimean War was the world’s “first armchair war,” a drama and spectacle that reached audiences around the world in something akin to “real time” by way of new technologies like the telegraph. It ended with Russia’s defeat, but in the Western popular imagination, the war served to mingle Crimea and Russia on our mental maps. The effect has been lasting.

凯瑟琳去世数十年后,俄罗斯的扩张停止了。19 世纪中叶,克里米亚成为帝国巨头的冲突地,英国、奥斯曼和欧洲盟友在黑海地区与俄罗斯争夺控制权。克里米亚战争是世界上“第一场扶手椅战争”,一场通过电报等新技术在类似“实时”中向全球观众传达的戏剧和壮观。战争以俄罗斯的失败告终,但在西方流行想象中,这场战争使克里米亚和俄罗斯在我们的心理地图上交织在一起。这种影响是持久的。

Despite defeat, the tsars held on to Crimea. But they never let go of anxieties about their control of the territory of the former Crimean Tatar khanate. In 1857, Tsar Aleksandr II took drastic measures to tighten his grip and explicitly ordered “the cleansing of the Tatars from the entire Crimean peninsula” and their replacement by Slavic “peasants from internal provinces” of the empire. At this time Crimean Tatars constituted nearly 80 percent of Crimea’s inhabitants. By 1900 they plummeted to roughly 25 percent of the population.

尽管遭到失败,沙皇们仍然紧抓克里米亚不放。但他们从未放松对前克里米亚鞑靼汗国领土控制的焦虑。1857 年,沙皇亚历山大二世采取了严厉措施来加强他的控制,并明确下令“将鞑靼人从整个克里米亚半岛清除”,并由帝国“内部省份的斯拉夫农民”取而代之。当时,克里米亚鞑靼人几乎占了克里米亚居民的 80%。到了 1900 年,他们的人口比例骤降至大约 25%。

In the 20th century, Stalin sought to finish what Aleksandr II started. In May 1944, after the Nazis had retreated, Stalin deported the remaining Crimean Tatar population — approximately 200,000 people — to Central Asia and other far-flung parts of the Soviet Union. The sick and injured not fit for transit on train cars originally meant for livestock were “liquidated.” Those who openly defied the deportation order were shot. Stalin’s Crimean atrocity ultimately claimed tens of thousands of lives. Survivors spent the next half century in places like Uzbekistan fighting for the right to return to their homeland, which they won in the twilight of the Soviet period.

在 20 世纪,斯大林试图完成亚历山大二世开始的事业。1944 年 5 月,纳粹撤退后,斯大林将剩余的克里米亚鞑靼人口——大约 20 万人——驱逐到中亚和苏联的其他遥远地区。不适合在原本用于运送牲畜的火车车厢中转运的病弱者被“清除”。那些公然抗命不遵从驱逐令的人被枪杀。斯大林的克里米亚暴行最终夺去了数以万计的生命。幸存者在接下来的半个世纪里,在乌兹别克斯坦等地为重返故土的权利而斗争,他们在苏联时期的末期赢得了这一权利。

Stalin turned what had been a rudimentary system of ethnic cleansing under the tsars into a brutally efficient machine aimed at decimating the past as well as the present. Our maps today bear evidence of this destruction. Before 1944 there were around 2,000 towns and villages in Crimea bearing Crimean Tatar names. After the deportation, only a relative handful remained. Stalin consigned traces of the legacy of the Crimean Tatars to what Orwell would call a “memory hole.”

斯大林将沙皇时期原始的种族清洗系统转变为旨在摧毁过去和现在的残酷高效机器。我们今天的地图上留下了这种破坏的证据。1944 年之前,克里米亚有大约 2000 个带有克里米亚鞑靼名字的城镇和村庄。在遣送之后,只有少数幸存下来。斯大林将克里米亚鞑靼的遗产痕迹置于奥威尔所说的“记忆黑洞”。

These changes took place with great speed. After demoting Crimea from the status of an Autonomous Republic to a mere oblast or “province” of Soviet Russia, Communist Party authorities ordered that Crimean Tatar names of cities, towns and villages be replaced with Russian ones. The daunting task fell to one man, the executive secretary of the newspaper Red Crimea, who had to rename a territory roughly the size of Massachusetts virtually overnight. For ideas, he flipped through a 19th-century fruiticulture book, on the one hand, and an account of the Red Army’s Crimean offensive against the Nazi Wehrmacht on the other.

这些变化发生得非常快。在将克里米亚的地位从自治共和国降为苏维埃俄国的一个普通州或“省”之后,共产党当局下令将克里米亚鞑靼人的城市、镇和村庄名称更换为俄罗斯名称。这项艰巨的任务落在了一名男子身上,他是报纸《红色克里米亚》的执行秘书,不得不在一个晚上的时间内重新命名一个与马萨诸塞州差不多大小的地区。为了寻找灵感,他一方面翻阅了一本 19 世纪的果树栽培书,另一方面则查看了红军对纳粹德国国防军在克里米亚的进攻记录。

That is why the names of so many places in Crimea strike visitors as bland and unimaginative today. Kiçkene, a village near Simferopol with only 156 recorded residents in 1939, became Malenkoe, “Smallville.” Qutlaq, a village in the Sudak region first cited in historical records in the 15th century, had a majority population of 1,636 Crimean Tatars in 1939. For assisting the Soviet partisan movement during the war, its residents had to watch as Nazi occupiers retaliated by burning the village to the ground. Qutlaq was renamed Veseloe, “Happytown.”

这就是为什么如今克里米亚许多地方的名字给游客的印象是平淡无奇和缺乏想象力。位于辛菲罗波尔附近的小村庄 Kiçkene,在 1939 年仅有 156 名居民记录,后来被改名为 Malenkoe,“小镇”。Qutlaq 是苏达克地区的一个村庄,最早在 15 世纪的历史记录中被提到,1939 年时有 1,636 名克里米亚鞑靼人占多数。在战争期间,由于协助苏联游击队,村民们不得不眼睁睁看着纳粹占领者报复性地将村庄烧毁。Qutlaq 后来被改名为 Veseloe,“快乐镇”。

This campaign to efface the Crimean Tatar people from Crimea — both physically and symbolically — intersected with a campaign to replace them. Between 1944 and 1946 alone, the Kremlin distributed stolen Crimean Tatar homes and property to roughly 64,000 settlers who arrived from other Soviet oblasts. Tens of thousands more arrived in the 1950s. Stalinist officials explicitly described this project in revealing terms. It was an initiative “to make Crimea a new Crimea with its own Russian form.”

这场旨在从克里米亚抹去克里米亚鞑靼人的存在——无论是物理上还是象征上的——的运动与一场取而代之的运动交织在一起。仅在 1944 年至 1946 年间,克里姆林宫就将被掠夺的克里米亚鞑靼人的房屋和财产分配给了大约 64,000 名从其他苏维埃州迁来的定居者。1950 年代又有成千上万的人抵达。斯大林主义官员明确地用揭示性的术语描述了这个项目。这是一个“使克里米亚成为具有自己的俄罗斯形式的新克里米亚”的倡议。

Such statements from Soviet authorities implicitly acknowledge that, prior to the 1940s, Crimea did not have a “Russian form.” They give the lie to claims that Crimea is “primordial” Russian territory, as Putin likes to insist. In the 1950s, the poet Boris Chichibabin walked through Crimea’s old Tatar streets and put it bluntly: “This is not Russia at all.”

苏维埃当局的这些声明暗示承认,在 1940 年代之前,克里米亚并没有“俄罗斯形态”。它们揭穿了克里米亚是“自古以来”的俄罗斯领土的说法,正如普京喜欢坚称的那样。在 1950 年代,诗人鲍里斯·契契巴宾走过克里米亚的老塔塔尔街道,直言不讳地说:“这根本就不是俄罗斯。”

Another truth about Crimea that Russians work hard to dismiss and conceal today is the peninsula’s dependence on the Ukrainian mainland.

克里米亚半岛依赖乌克兰本土是俄罗斯人今天努力忽视和掩盖的另一个事实。

But Stalin’s successor, Nikita Khrushchev, learned the lesson up close and personal. In 1953 he travelled to Crimea with his son-in-law, the prominent Soviet journalist Aleksei Adzhubei. The trip was no vacation. According to Adzhubei, Khrushchev had a series of awkward encounters with crowds of post-war Soviet settlers, who made desperate pleas for more material assistance. Khrushchev was frustrated by all the complaints. “Why did you come here anyway?” Adzhubei recalls Khrushchev asking the settlers. “We were tricked!” they replied.

但斯大林的继任者尼基塔·赫鲁晓夫亲身学到了这个教训。1953 年,他和他的女婿、著名苏联记者阿列克谢·阿兹朱别一起前往克里米亚。这趟旅行并非度假。据阿兹朱别回忆,赫鲁晓夫在与一群战后苏联移民的尴尬接触中,不断听到他们对更多物质援助的迫切请求。赫鲁晓夫对所有这些抱怨感到沮丧。“你们为什么要来这里?”阿兹朱别记得赫鲁晓夫问移民们。“我们被骗了!”他们回答说。

Adzhubei described Crimea at the time as a deeply “desolate” region still struggling to rebound from Nazi occupation and what he called Stalin’s “Tatar genocide,” which had not only depopulated the peninsula but deprived it of agricultural know-how in the cultivation of vineyards and tobacco fields.

阿朱别当时描述克里米亚为一个深度“荒凉”的地区,仍在努力从纳粹占领中恢复过来,以及他所说的斯大林的“鞑靼种族灭绝”,这不仅使半岛人口锐减,还剥夺了它在葡萄园和烟草田种植方面的农业知识。

By all accounts, the bleak conditions in Crimea shocked Khrushchev. According to Dmitrii Polianskii, who served as head of the Communist Party in Crimea between 1953 and 1954, Khrushchev came to the conclusion that “Russia had paid little attention to Crimea’s development” and that “Ukraine could handle it more concertedly.”

根据所有的描述,克里米亚的凄凉状况震惊了赫鲁晓夫。据曾在 1953 年至 1954 年间担任克里米亚共产党负责人的德米特里·波利扬斯基所说,赫鲁晓夫得出结论:“俄罗斯对克里米亚的发展关注甚少”,并且“乌克兰可以更有条不紊地处理这一问题。”

Khrushchev and other Soviet authorities learned the hard way that Crimea is not an “island” or a “jewel,” as Russian metaphors would have it, a beautiful but self-sufficient swath of territory. Instead, to reach for another metaphor, Crimea is a flower whose blossom floats in the Black Sea and whose stem reaches deep into the Ukrainian steppe, into the territory around today’s frontline cities of Kherson, Melitopol’, and Mariupol’.

赫鲁晓夫和其他苏联当局通过艰难的方式了解到,克里米亚不是俄罗斯比喻中的“岛屿”或“珠宝”,一个美丽但自给自足的地域。相反,用另一个比喻来说,克里米亚是一朵花,它的花朵在黑海上漂浮,它的茎深深扎入乌克兰大草原,延伸到如今前线城市赫尔松、梅利托波尔和马里乌波尔周围的领土。

The Crimean Tatars used to refer to this steppeland as the Özü qırları or Özü çölleri, the “Dnipro fields.” The reference to the Dnipro (or Dnieper), Ukraine’s largest river, was not ornamental. The Crimean peninsula is largely arid and warm, lacking abundant fresh water of its own. For centuries it has thirsted for the Dnipro’s water and relied on resource flows from mainland Ukraine.

克里米亚鞑靼人曾将这片草原称为Özü qırları或Özü çölleri,即“第聂伯河田野”。提到第聂伯河(或称为尼珀尔河),乌克兰最长的河流,并非仅仅是装饰性的。克里米亚半岛大部分地区干旱炎热,缺乏充足的自有淡水资源。几个世纪以来,它一直渴望第聂伯河的水,并依赖来自乌克兰本土的资源流。

In February 1954, Khrushchev’s regime took action to rejoin the blossom to its stem, announcing the formal transfer of the Crimean oblast from Soviet Russia to Soviet Ukraine. During the formal Politburo proceedings, Soviet Russian politician Mikhail Tarasov justified the transfer by describing Crimea in the way we should understand it today: as “a natural continuation of Ukraine’s southern steppe.”

1954 年 2 月,赫鲁晓夫政权采取行动将花朵重新接回其茎干,宣布正式将克里米亚州从苏联俄罗斯转移到苏联乌克兰。在正式的政治局会议上,苏联俄罗斯政治家米哈伊尔·塔拉索夫为转移行为辩护,他描述克里米亚应该被我们今天理解的方式:作为“乌克兰南部草原的自然延续”。

Adzhubei called the transfer a “business transaction” directed toward Crimea’s economic development. It produced quick dividends. In 1957, Ukrainian authorities in Kyiv oversaw the launch of what had been decades earlier merely a Russian pipedream: the construction of the North Crimean Canal, which expedited flows from the Dnipro river near Kherson to irrigate the entire peninsula. Crimea’s economy, particularly its agricultural sector, improved dramatically. So did its tourism industry. High-rise sanatoria for the Soviet elite popped up along the southern coast, driving the image of a Soviet Shangri-La along the Black Sea.

阿朱别称这次转移是一次“商业交易”,旨在促进克里米亚的经济发展。这笔交易很快产生了回报。1957 年,乌克兰当局在基辅监督启动了几十年前仅仅是俄罗斯的一个梦想:北克里米亚运河的建设,该运河从靠近赫尔松的第聂伯河加快了水流,灌溉了整个半岛。克里米亚的经济,特别是其农业部门,得到了显著改善。其旅游业也是如此。苏联精英的高层疗养院沿着南部海岸线涌现,打造了一幅黑海沿岸的苏维埃香格里拉的形象。

Only in later years would Ukraine’s success in developing Crimea be denigrated and mythologized as Khrushchev’s “gift” of Crimea to Ukraine – or worse, as Khrushchev’s “mistake.” The transfer of Crimea to Ukraine was no mistake. It was a rescue.

仅在后来的岁月里,乌克兰在发展克里米亚的成功才被贬低,并被神话化为赫鲁晓夫将克里米亚“赠送”给乌克兰的“礼物”——或者更糟,被视为赫鲁晓夫的“错误”。克里米亚转交给乌克兰并非错误。这是一次营救。

Connecting the dots between Crimea’s geography, history and scarred demography helps explain some of the trajectories of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. It also illustrates the need for Ukraine’s absolute victory.

连接克里米亚的地理、历史和饱受创伤的人口统计之间的点,有助于解释俄罗斯对乌克兰侵略行径的一些轨迹。这也说明了乌克兰绝对胜利的必要性。

Putin’s 2014 annexation operation ended up disconnecting Crimea from resource flows from Ukraine, including the North Crimean Canal, which still supplied 85 percent of fresh water to the peninsula. His massive vanity bridge, stretching 12 miles over the Kerch Strait from the eastern edge of Crimea to mainland Russia, was completed in 2018 but could not come close to compensating for these losses. That’s why in February 2022 — on the very first day of the full-scale invasion — Putin’s forces used Crimea as a launchpad to tear into Ukraine’s Kherson oblast and seize control of this critical water and resource supply. The move was an implicit recognition of a fundamental reality: Crimea needs to be connected to the Ukrainian mainland to thrive or even survive.

普京 2014 年的吞并行动最终导致克里米亚与乌克兰的资源流动断开,包括北克里米亚运河,该运河仍然为半岛提供了 85%的淡水。他那座横跨刻赤海峡、从克里米亚东缘延伸至俄罗斯大陆的长达 12 英里的巨型虚荣桥在 2018 年完工,但这座桥远远无法弥补这些损失。这就是为什么在 2022 年 2 月——全面入侵的第一天——普京的军队使用克里米亚作为跳板,撕裂乌克兰的赫尔松州并控制这一关键的水资源供应。此举是对一个基本现实的含蓄承认:克里米亚需要与乌克兰大陆相连,才能繁荣甚至生存。

Russia’s hold on Crimea is, therefore tenuous. Any proposed peace settlement that codifies its occupation in exchange for a cessation of hostilities would be a ticking time bomb. The truth is that Ukraine will never be stable and peaceful with a Russian-occupied Crimea, and a Russian-occupied Crimea will never be resource-secure without Ukraine.

因此,俄罗斯对克里米亚的控制是脆弱的。任何旨在通过确认其占领地位以换取停止敌对行动的和平解决方案都将是一个定时炸弹。事实是,只要克里米亚被俄罗斯占领,乌克兰就永远不会稳定与和平,而一个被俄罗斯占领的克里米亚也永远不会在没有乌克兰的情况下实现资源安全。

Crimean Tatar activist and Amnesty International prisoner of conscience Emir-Usein Kuku frames the problem with a sardonic question that refers to the Russian security and intelligence agency, the FSB.

克里米亚鞑靼活动家和国际特赦组织良心犯埃米尔-乌谢因·库库用一个讽刺的问题来描述这个问题,这个问题涉及俄罗斯安全和情报机构,即联邦安全局(FSB)。

“Doesn’t it seem strange,” he asked during his illegal trial in Russia in 2019, “that in the 23 years under Ukrainian authority in Crimea there were no ‘extremists,’ no ‘terrorists,’ and no ‘acts of terror’ for that matter? But then Russia arrived with its FSB, and suddenly all of these things appeared together?”

“在俄罗斯 2019 年的非法审判中,他问道,‘这难道不奇怪吗?在克里米亚处于乌克兰管辖的 23 年里,没有‘极端分子’,没有‘恐怖分子’,也没有‘恐怖行为’。但是随后俄罗斯带着它的联邦安全局来了,突然所有这些事情一起出现了?’”

The track record is clear. Ukraine stabilized Crimea; Russia has turned it into a hinge of expansionist aggression. In 2014 the world stood by and let it happen in the vain hope of easy peace.

轨迹清晰可见。乌克兰稳定了克里米亚;俄罗斯却将其变成了扩张侵略的枢纽。2014 年,世界在徒劳希望和平的幻想中袖手旁观,任由这一切发生。

We cannot afford to make the same mistake now. Half-measures and short-sighted compromises are a recipe for endless war against a state bent on savage imperialist conquest. The difficult path to lasting peace is Ukraine’s de-occupation of Crimea and an unmistakable defeat of Russian aggression.

我们现在不能再犯同样的错误。折中措施和目光短浅的妥协是对抗一个致力于野蛮帝国主义征服的国家的无休止战争的食谱。通往持久和平的艰难道路是乌克兰对克里米亚的去占领以及对俄罗斯侵略行为的明确失败。

Europe and the United States should know well the urgency of a total defeat of the aggressor. In his address to Congress in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Franklin Delano Roosevelt pledged that, “no matter how long it may take us to overcome this premeditated invasion, the American people in their righteous might will win through to absolute victory.”

欧洲和美国应该清楚地认识到彻底击败侵略者的紧迫性。1941 年 12 月珍珠港袭击事件发生后,富兰克林·德拉诺·罗斯福在对国会的演讲中承诺:“无论我们需要多长时间来克服这一预谋的入侵,美国人民凭借他们正义的力量将会取得绝对的胜利。”

Now as then, only absolute victory will do. Only a defeated, demilitarized Russia and a fully liberated Ukraine — whole and integral within its internationally recognised borders — can promise long-term stability and an enduring peace.

如今如同过去,唯有彻底的胜利才算数。只有一个被击败、去军事化的俄罗斯,以及一个完全解放的、在其国际公认边界内完整无缺的乌克兰,才能保证长期稳定和持久和平。