Xi Jinping’s Russian Lessons | Foreign Affairs

习近平的俄罗斯课 | 《外交事务》

By Joseph Torigian June 24, 2024

Joseph Torigian is an assistant professor at the School of International Service at American University in Washington, a global fellow in the History and Public Policy Program at the Wilson Center, and a Center associate of the Lieberthal-Rogel Center for Chinese Studies at the University of Michigan. Previously, he was a visiting fellow at the Australian Center on China in the World at Australian National University, a Stanton Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, a postdoctoral fellow at the Princeton-Harvard China and the World Program, a postdoctoral (and predoctoral) fellow at Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation, a predoctoral fellow at George Washington University’s Institute for Security and Conflict Studies, an IREX scholar affiliated with the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, and a Fulbright Scholar at Fudan University in Shanghai. His book Prestige, Manipulation, and Coercion: Elite Power Struggles in the Soviet Union and China after Stalin and Mao was published in 2022 by Yale University Press, and he has a forthcoming biography on Xi Jinping’s father with Stanford University Press. He studies Chinese and Russian politics and foreign policy.

约瑟夫·托里吉安是华盛顿美利坚大学国际服务学院的助理教授,威尔逊中心历史与公共政策项目的全球研究员,以及密歇根大学李伯塔尔-罗杰尔中国研究中心的研究员。他曾是澳大利亚国立大学澳大利亚中国研究中心的访问学者、外交关系委员会的斯坦顿学者、普林斯顿-哈佛中国与世界项目的博士后研究员、斯坦福国际安全与合作中心的博士后(及博士前)研究员、乔治华盛顿大学安全与冲突研究所的博士前研究员、莫斯科高等经济学院的IREX学者,以及复旦大学的富布赖特学者。他的著作《声望、操控与胁迫:斯大林和毛泽东之后的苏联和中国的精英权力斗争》于2022年由耶鲁大学出版社出版,他即将出版一本关于习近平父亲的传记,由斯坦福大学出版社出版。他的研究领域包括中国和俄罗斯的政治和外交政策。

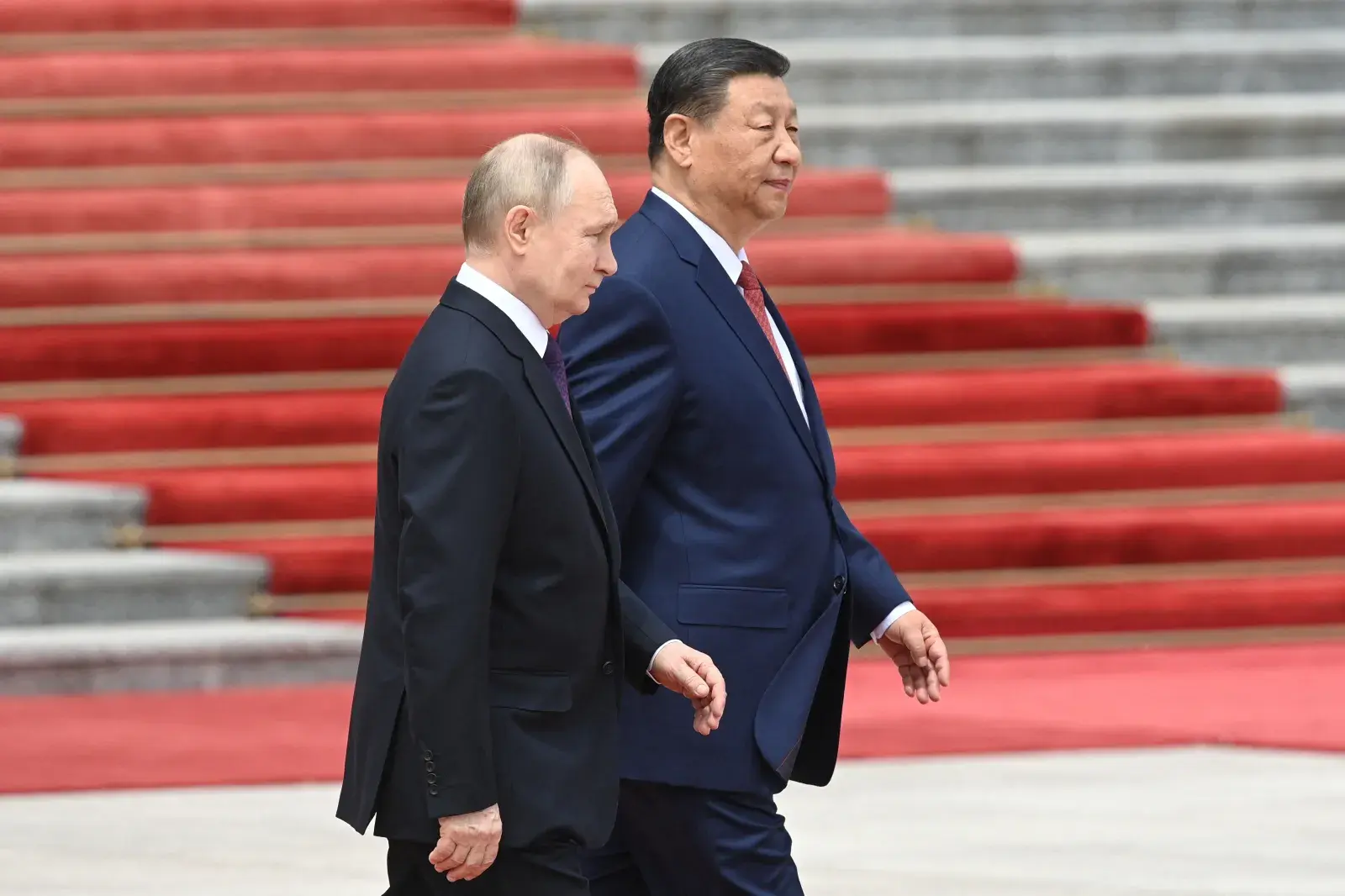

On February 4, 2022, just before invading Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin traveled to Beijing, where he and Chinese leader Xi Jinping signed a document that hailed a “no limits” partnership. In the two-plus years since, China has refused to condemn the invasion and helped Russia acquire materiel, from machine tools to engines to drones, crucial for the war effort. The flourishing partnership between Xi and Putin has raised serious questions in Western capitals. Is the alliance that linked Moscow and Beijing in the early Cold War back? The Russians and the Chinese have repeatedly dismissed such talk, but they have also asserted that their current partnership is more resilient than the days when they led the communist world together.

2022年2月4日,就在入侵乌克兰前夕,俄罗斯总统弗拉基米尔·普京前往北京,与中国领导人习近平签署了一份宣称“无上限”伙伴关系的文件。在随后的两年多里,中国拒绝谴责这次入侵,并帮助俄罗斯获取从机床到发动机再到无人机等对战争努力至关重要的物资。习近平与普京之间蓬勃发展的伙伴关系在西方各国首都引发了严重质疑。冷战初期将莫斯科和北京联系在一起的联盟又回来了?俄罗斯和中国多次驳斥这种说法,但他们也断言,目前的伙伴关系比他们曾一起领导共产主义世界的时代更加坚韧。

Xi would know. His father, Xi Zhongxun, was a high-level Chinese Communist Party (CCP) official whose own career was a microcosm of relations between Beijing and Moscow during the twentieth century, from the early days of the revolution in the 1920s and 1930s to the on-and-off help during the 1940s and the wholesale copying of the Soviet model in the 1950s, and from the open split of the 1960s and 1970s to the rapprochement in the late 1980s. The elder Xi’s dealings with Moscow showed the dangers of intimacy and enmity, how growing too close created unmanageable tensions that produced a costly feud. Understanding that history, the younger Xi by all appearances believes that the current relationship between Moscow and Beijing is indeed stronger than it was in the 1950s, and that he can avoid the strains that led to the earlier split.

习近平深知这一点。他的父亲习仲勋是中国共产党高级官员,他的职业生涯是二十世纪中苏关系的缩影,从20世纪20年代和30年代革命初期,到40年代的断断续续的援助,再到50年代对苏联模式的全面复制,从60年代和70年代的公开决裂到80年代末的和解。习仲勋与莫斯科的交往显示了亲密和敌意的危险,过于亲近会导致难以管理的紧张局势,从而引发代价高昂的争斗。了解这段历史,习近平显然认为目前的中俄关系确实比50年代更强,他可以避免导致先前分裂的压力。

During the Cold War communist ideology ultimately pushed the two countries apart, while now they are united by a more general set of conservative, anti-Western, and statist attitudes. In the old days, poor relations between individual leaders damaged the relationship, while today, Xi and Putin have made their personal connection a feature of the strategic partnership. Then, the exigencies of the Cold War alliance, which required each side to sacrifice its own interests for the other’s, contained the seeds of its own demise, whereas the current axis of convenience allows more flexibility. China and Russia will never again march in lockstep as they did in the first years after the Chinese Revolution, but they won’t walk away from each other any time soon.

在冷战期间,共产主义意识形态最终将两国分裂,而现在他们则因更广泛的保守、反西方和国家主义态度而团结。在过去,领导人之间糟糕的关系损害了两国关系,而今天,习近平和普京把他们的个人联系作为战略伙伴关系的一部分。那时,冷战联盟的紧迫性要求双方为对方牺牲自己的利益,这也埋下了它自己毁灭的种子,而现在的便利轴心则允许更多的灵活性。中俄永远不会像中国革命初期那样步调一致,但他们也不会很快分道扬镳。

DANGEROUS LIAISONS 危险的关系

Xi Jinping was born in 1953, at the height of China’s feverish copying of the Soviet Union. The most popular slogan in China that year: “The Soviet Union of today is the China of tomorrow.” Xi Zhongxun had just moved to Beijing from China’s northwest, where he had spent most of the first four decades of his life fighting in a revolution inspired by the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. Like so many of his generation, Xi was devoted to the cause despite numerous setbacks and personal sacrifices—a devotion that survived his persecution and incarceration by fellow members of the CCP in 1935 for not adhering closely enough to communist orthodoxy.

习近平出生于1953年,正值中国热衷于效仿苏联的巅峰时期。当年中国最流行的口号是:“今天的苏联就是明天的中国。”习仲勋刚从中国西北迁到北京,他在西北度过了大部分人生的前四十年,参加了受到1917年布尔什维克革命启发的革命。和他那一代的许多人一样,尽管经历了无数挫折和个人牺牲,习对这项事业始终忠诚——这种忠诚使他在1935年因未能严格遵循共产主义正统而被党内同志迫害和监禁后仍未动摇。

The Bolshevik victory influenced early Chinese radicals, and Moscow led and bankrolled the CCP in its early years. But the growing independence of the Chinese Communists went hand in hand with the rise of Mao Zedong—and tied Xi Zhongxun’s fate to Mao’s. In Mao’s narrative, Soviet-trained radicals had almost buried the revolution in China because they had failed to understand the country’s special conditions. These dogmatists, Mao claimed, had persecuted Xi in 1935 just as they had mistreated Mao himself earlier that decade, when Mao was sidelined by Soviet-aligned leaders in the CCP.

布尔什维克的胜利影响了早期的中国激进分子,莫斯科在中共早期领导和资助了该党。但中国共产党日益增长的独立性与毛泽东的崛起密不可分,并将习仲勋的命运与毛的命运联系在一起。根据毛的说法,苏联训练的激进分子几乎使中国革命夭折,因为他们未能理解中国的特殊情况。毛声称,这些教条主义者在1935年迫害了习,就像他们在本世纪早些时候冷落毛自己一样,当时毛被党内亲苏领导人排挤。

Xi and Putin have made their personal connection a feature of the strategic partnership.

习近平和普京已将他们的个人联系作为战略伙伴关系的一部分。

Nonetheless, Mao was not advocating a break from Moscow. Xi Zhongxun met very few foreigners for most of his early life, but that changed in the late 1940s, as the Communists swept across China during the country’s civil war. He started having sustained interactions with Soviets as the head of the enormous Northwest Bureau, the party organization that oversaw the Xinjiang region. The Soviet Union helped the CCP project military power there, and in December 1949, after the Communists had won the war and consolidated control over mainland China, Xi successfully proposed to the party’s leaders that Xinjiang and the Soviet Union cooperate to develop resources in the province. A year later, Xi became head of the Northwest Chinese-Soviet Friendship Association.

尽管如此,毛并不主张与莫斯科决裂。习仲勋在早年生活中很少接触外国人,但这种情况在1940年代末发生了变化,随着共产党人在国内战争中席卷中国,他开始与苏联人进行持续互动。作为监督新疆地区的庞大西北局的负责人,他开始与苏联人频繁接触。苏联帮助中共在那里投射军事力量,1949年12月,在共产党赢得战争并巩固对中国大陆的控制后,习成功向党的领导人提议,新疆与苏联合作开发该省资源。一年后,习成为西北中苏友好协会的负责人。

Right around the time of Xi Jinping’s birth, the CCP undertook its first great purge—an incident closely linked to both the Soviet Union and the Xi family. Gao Gang, a high-level official who was seen as a potential successor to Mao, went too far in his criticisms of other leaders during private conversations. Mao turned on his protégé, and Gao eventually committed suicide. Gao had close ties to Moscow, and although they were not the reason for his purge at the time, Mao came to worry about such connections and concluded that they amounted to treachery. The danger of close relations with a foreign power, even an ally, could not have been lost on Xi Zhongxun, who had served alongside Gao in the northwest and had been persecuted along with him in 1935. Xi nearly fell along with him.

就在习近平出生前后,中共进行了第一次大清洗——这一事件与苏联和习家族密切相关。高级官员高岗在私下谈话中对其他领导人批评过度,被视为毛的潜在接班人。毛转而反对他的门徒,高最终自杀。高与莫斯科关系密切,尽管这不是他被清洗的原因,但毛开始担心这种关系,并认为这相当于背叛。与外国势力的密切关系,甚至是盟友,不可能没有让习仲勋意识到危险。习曾在西北与高一起工作,1935年也与高一起被迫害。习差点和高一起倒下。

Although Xi Zhongxun’s career was hurt by Gao’s misfortune, he was later put in charge of managing the tens of thousands of Soviet experts sent to help China rebuild after years of war. That was no easy task. As Xi recounted in a 1956 speech, these experts had a hard time acclimating to China, and some of them had “died, been poisoned, been injured, gotten sick, and robbed”—even suicide was a problem. When Mao decided that same year that the Chinese political structure was too “Soviet” and concentrated too much authority in Beijing, Xi was also tasked by the leadership to devise a government-restructuring plan.

尽管高的厄运损害了习仲勋的职业生涯,但后来他负责管理数万名帮助中国重建的苏联专家。这并非易事。正如习在1956年的一篇演讲中所回忆的那样,这些专家很难适应中国,有些人“死亡、中毒、受伤、生病、被抢劫”——甚至自杀也是个问题。同年,当毛决定中国的政治结构过于“苏联化”并将过多权力集中在北京时,习也被领导层委托制定政府重组计划。

SPLITTING UP 分道扬镳

In August and September 1959, Xi, then a powerful vice premier, led a delegation to the Soviet Union. The timing was inopportune. In June, the Soviets had reneged on a promise to support China’s nuclear weapons program. Xi was supposed to visit the Soviet Union earlier in the summer of that year, but a CCP plenum in Lushan—where Minister of Defense Peng Dehuai was purged—shattered those plans. Peng had written a letter to Mao criticizing the Great Leap Forward, and Mao not only interpreted Peng’s act as a personal affront but also suspected, incorrectly, that Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev had put him up to it. Peng and Xi were linked by career ties forged on the battlefield for northwest China. The CCP’s second great purge, just like the first, was both proximate to the Xi family and tied to Mao’s suspicions of Soviet intentions. And once again, Xi only narrowly survived.

1959年8月和9月,时任副总理的习仲勋率领代表团访问苏联。时机并不合适。6月,苏联违背了承诺,不再支持中国的核武器计划。习本应在当年夏初访问苏联,但中共中央在庐山召开的全会——在会上国防部长彭德怀被清洗——打乱了这一计划。彭德怀给毛泽东写了一封信,批评大跃进,毛不仅将彭的行为视为个人冒犯,还错误地怀疑苏联领导人尼基塔·赫鲁晓夫指使了彭。彭和习在西北战场上建立了职业关系。中共的第二次大清洗,与第一次一样,与习家族紧密相关,并与毛对苏联意图的怀疑有关。而习再次勉强幸存下来。

Since 1956, Sino-Soviet tensions had been growing gradually behind the scenes, but they broke out publicly during Xi’s trip. On August 25, the same day the Soviet embassy in Beijing invited Xi on his visit, Chinese soldiers killed one Indian soldier and wounded another on the Chinese-Indian border. Although the Chinese concluded that the deaths were accidental, the Soviets were incensed, because they believed that the violence would push the Indians away from the communist bloc and frustrate Khrushchev’s attempts to achieve détente with the West during an upcoming trip to Washington.

自1956年以来,中苏紧张关系逐渐在幕后加剧,但在习的访问期间公开爆发。8月25日,就在苏联大使馆邀请习访问的同一天,中国士兵在中印边境打死了一名印度士兵,打伤了另一名。尽管中国认为死亡是意外的,但苏联人非常愤怒,因为他们认为这种暴力会将印度人推离共产主义阵营,并挫败赫鲁晓夫在即将到来的华盛顿之行中实现缓和的努力。

Arriving in Moscow two days after the violence on the border, Xi did his best to affirm the alliance. In a private meeting with a Soviet vice premier, he tried to put a positive spin on Mao’s Great Leap Forward, then one year in. He visited the Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy, a showcase for Soviet technological triumphs, and placed a wreath at the mausoleum of the Soviet Union’s first two leaders, Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin. After spending a few days in Soviet Ukraine and Czechoslovakia, Xi returned to Moscow, where his delegation toured Lenin’s old office and apartment in the Grand Kremlin Palace. He apparently told his son about the moment: in 2010, when Xi Jinping visited Moscow as vice president, he asked Russian President Dmitry Medvedev to take him to the same room. According to a well-connected Russia expert, Xi lingered there, telling Medvedev that this was the cradle of Bolshevism. His father, Xi claimed, had said that Russia and China should always be friends.

在边境暴力事件发生两天后抵达莫斯科,习尽力确认联盟。在与苏联副总理的私人会议上,他试图对毛的一年多的“大跃进”进行积极解读。他参观了国民经济成就展览馆,一个展示苏联技术成就的地方,并在苏联的两位首任领导人弗拉基米尔·列宁和约瑟夫·斯大林的陵墓前献了花。在苏联乌克兰和捷克斯洛伐克呆了几天后,习返回莫斯科,他的代表团参观了列宁在克里姆林宫大厦的旧办公室和公寓。他显然将这一时刻告诉了他的儿子:2010年,当习近平以副主席身份访问莫斯科时,他请俄罗斯总统德米特里·梅德韦杰夫带他去同一个房间。根据一位消息灵通的俄罗斯专家的说法,习近平在那里流连,告诉梅德韦杰夫这是布尔什维克主义的摇篮。他声称,他的父亲曾说,俄罗斯和中国应该永远是朋友。

Yet in 1959, Xi Zhongxun was in the middle of a crisis in the relationship. On September 9, back in Beijing, Soviet diplomats informed the Chinese about plans to publish a statement in TASS, the state-owned news agency, that took a neutral position on the Chinese-Indian border skirmish. The Chinese were furious and asked the Soviets to change or delay the bulletin. The Soviets not only refused their request but published the statement that evening. Xi left for Beijing the very next day—even though he was supposed to continue leading the delegation until September 18. When Mao and Khrushchev met the following month, Mao complained about the incident, saying, “The TASS announcement made all imperialists happy.”

然而在1959年,习仲勋正处于关系危机的中心。9月9日,回到北京,苏联外交官通知中国计划在国营新闻机构塔斯社发表声明,对中印边境冲突采取中立立场。中国人大为恼火,要求苏联修改或推迟公告。苏联不仅拒绝了他们的要求,还在当晚发表了声明。习第二天就离开了北京——尽管他原本应继续带领代表团直到9月18日。毛和赫鲁晓夫下个月会晤时,毛抱怨此事,说:“塔斯社的声明让所有帝国主义者都高兴。”

The dispute was merely the first public crack in the alliance. In the summer of 1960, Khrushchev removed all Soviet experts from China, and Xi was placed in charge of managing their departure. The lesson his son drew from the episode was that the Chinese needed to rely on themselves. At a November 2022 meeting in Bali, according to a former senior U.S. diplomat, Xi Jinping told U.S. President Joe Biden that American technological restrictions would fail, pointing out that the Soviets’ cessation of technological cooperation had not prevented China from developing its own nuclear weapons.

这场争端仅仅是联盟首次公开裂痕。1960年夏天,赫鲁晓夫撤回了所有在华苏联专家,习负责管理他们的撤离。他的儿子从这次事件中得出的教训是,中国需要依靠自己。根据一位前美国高级外交官的说法,2022年11月在巴厘岛的一次会议上,习近平告诉美国总统乔·拜登,美国的技术限制将失败,并指出苏联停止技术合作并未阻止中国发展自己的核武器。

HOT AND COLD 冷与热

In 1962, Xi Zhongxun’s luck ran out, and he was expelled from power in the CCP’s third great purge. Just like Gao and Peng, he was accused of spying for the Soviet Union, although that was not the primary reason for his punishment. Mao had decided that China, like the Soviet Union before it, was losing its fixation on class struggle, and Xi was caught up in destruction that Mao wrought in reaction. In 1965, while Mao was planning a costly reorganization of Chinese society to fight a possible war against the Soviet Union or the United States, Xi was exiled from Beijing to a mining machinery factory hundreds of miles away in the city of Luoyang. Ironically, that factory had been completed with the help of Soviet experts and had even been described in a local newspaper as a “crystallization” of the “glorious Sino-Soviet friendship.”

1962年,习仲勋的好运用尽,在中共第三次大清洗中被驱逐出权力。像高岗和彭德怀一样,他被指控为苏联间谍,尽管这并不是他受罚的主要原因。毛泽东认为中国像之前的苏联一样,正在失去对阶级斗争的专注,习因此卷入了毛反应中所带来的破坏。1965年,当毛计划进行一场代价高昂的社会重组,以应对可能与苏联或美国的战争时,习被流放到几百英里外洛阳的一家矿山机械厂。讽刺的是,这家工厂是在苏联专家的帮助下建成的,甚至被当地报纸称为“光辉的中苏友谊的结晶”。

All told, Xi Zhongxun spent 16 years in the political wilderness. He had to wait until 1978, two years after Mao’s death, to be rehabilitated. As party boss of the province of Guangdong, Xi warned Americans that they needed to be strong to ward off Soviet aggression. On a trip to the United States in 1980, he impressed his U.S. counterparts with his anti-Soviet views and even made a trip to the headquarters of the North American Air Defense Command, or NORAD, in Colorado, where he took copious notes. As the Politburo member charged with managing relations with foreign parties that were revolutionary, leftist, or communist in nature, Xi helped lead Beijing’s competition for influence with Moscow throughout the world. He also managed Tibetan affairs, and in the first half of the 1980s, he worried about Soviet influence over the Dalai Lama. But by 1986, as ties thawed, Xi was praising the reforms of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and expressing hope for improved relations.

总而言之,习仲勋在政治荒野中度过了16年。直到毛泽东去世两年后的1978年,他才得以恢复名誉。作为广东省委书记,习警告美国人,他们需要保持强大以抵御苏联的侵略。1980年访问美国期间,他以反苏观点给美国同行留下深刻印象,甚至访问了位于科罗拉多州的北美防空司令部(NORAD)总部,并做了大量笔记。作为负责与具有革命性、左翼或共产主义性质的外国党派关系的政治局成员,习帮助领导了北京在全球范围内与莫斯科的影响力竞争。他还管理西藏事务,在80年代上半期,他担心苏联对达赖喇嘛的影响。但到1986年,随着关系解冻,习赞扬苏联领导人米哈伊尔·戈尔巴乔夫的改革,并表达了改善关系的希望。

What did Xi Jinping make of this history? In 2013, on his first overseas trip after becoming top leader, he went to Russia, where he spoke warmly to a group of Sinologists about his father’s 1959 visit. The pictures from that journey had been destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, he said, but his mother kept the gifts from it. Xi explained that although many observers believed that his generation was oriented toward the West, he was raised reading two literatures, Chinese and Russian. After Xi was exiled to the countryside as a “sent-down youth” during the Cultural Revolution, he spent his days reading Russian revolutionary novels, with a favorite being What Is to Be Done? by Nikolay Chernyshevsky. Xi later claimed to like the character Rakhmetov, the revolutionary fanatic who slept on nails to forge his will. Claiming inspiration, Xi said he wandered through rainstorms and blizzards during his time in the countryside.

习近平如何看待这段历史?2013年,在他成为最高领导人后的首次出访中,他前往俄罗斯,并热情地向一群汉学家讲述了他父亲1959年的访问。他说,那次旅程的照片在文革期间被毁,但他母亲保留了那些礼物。习解释说,尽管许多观察家认为他那一代人面向西方,但他是在阅读中俄两国文学中成长的。文革期间,习作为“下乡青年”被流放到农村时,他花时间阅读俄国革命小说,其中最喜欢的是尼古拉·车尔尼雪夫斯基的《怎么办?》。习后来声称喜欢革命狂热者拉赫梅托夫这个角色,拉赫梅托夫为了锻炼意志力在钉子上睡觉。受其启发,习说他在乡下时曾在暴风雨和暴风雪中徘徊。

But in his 2013 talk with the Russian Sinologists, he did not mention the dismal state of Sino-Soviet relations at the time of his Russian reading. In 1969, the year he was sent to the countryside, China and the Soviet Union were fighting an undeclared border war, and there were even fears of a Soviet nuclear attack. Nor did he tell them about his first job after graduating university, working as a secretary to Geng Biao, secretary-general of the Central Military Commission. Geng viewed Moscow warily. In 1980, at a meeting in Beijing, U.S. Secretary of Defense Harold Brown told Geng that when it came to the two sides’ views on the Soviet Union, “it seems to me, our respective staffs must have written our talking papers together.”

但在2013年与俄罗斯汉学家的谈话中,他没有提及他阅读俄国小说时中苏关系的惨淡状态。1969年,他被下放到农村时,中苏正在进行一场未宣战的边境战争,甚至有人担心苏联会进行核攻击。他也没有提到他大学毕业后的第一份工作,是担任中央军委秘书长耿飚的秘书。耿对莫斯科持谨慎态度。1980年,在北京的一次会议上,美国国防部长哈罗德·布朗告诉耿,在双方对苏联的看法上,“在我看来,我们各自的工作人员仿佛是一起写了我们的谈话稿。”

THE IDEOLOGICAL IRRITANT 意识形态的刺激

Given the state of relations among Russia, China, and the United States today, it is hard to imagine that Xi Jinping spent part of his teenage years digging an air-raid shelter in preparation for a possible Soviet attack—or for that matter, that his father had been invited to see NORAD. The fluidity of the Washington-Beijing-Moscow triangle over the last 75 years has led some to hope that Xi might somehow be convinced to rein in his support for Russia. But those wishing for a redux of the Sino-Soviet split are likely to be disappointed.

鉴于今天俄罗斯、中国和美国之间的关系,很难想象习近平在少年时代曾挖掘防空洞,以准备应对可能的苏联攻击——更不用说他父亲曾被邀请参观北美防空司令部。华盛顿-北京-莫斯科三角关系在过去75年的流动性让一些人希望,习近平可能会被说服限制对俄罗斯的支持。但那些期待中苏分裂重演的人可能会失望。

For one thing, the irritant of ideology is now mostly absent from the relationship. It is true that a common communist ideology served as an extraordinary glue for China and Russia in the years immediately after 1949. But as time went on, ideology actually made it harder for the two countries to manage their differences. Mao had a habit of interpreting tactical differences as deeper ideological disputes. The Soviets, Mao increasingly came to believe, did not support China’s combative position toward the West because they had gone “revisionist.” And among communists, charges of theoretical heresy were explosive. When Mao and Khrushchev fought over the TASS announcement in October 1959, it was Chinese Foreign Minister Chen Yi’s claim that the Soviets were “time-servers” that especially enraged Khrushchev, as it questioned his communist credentials by painting him as a traitor to the revolutionary enterprise. There is a lot of truth, then, to the historian Lorenz Luthi’s claim that “without the vital role of ideology, neither would the alliance have been established nor would it have collapsed.”

首先,意识形态的刺激现在大多已经不在这种关系中。确实,共同的共产主义意识形态在1949年后不久成为中国和俄罗斯之间一种非凡的纽带。但随着时间的推移,意识形态实际上使两国更难以处理分歧。毛习惯将战术分歧解读为更深层的意识形态争议。毛越来越认为,苏联人不支持中国对西方的对抗立场,因为他们已经变得“修正主义”。在共产党内部,理论异端的指控是爆炸性的。1959年10月,毛与赫鲁晓夫因塔斯社声明争执时,正是中国外交部长陈毅声称苏联人是“见风使舵”的言论激怒了赫鲁晓夫,因为这质疑了他的共产主义信条,将其描绘为革命事业的叛徒。因此,历史学家洛伦茨·卢西的说法有很多真相,即“没有意识形态的关键作用,这个联盟既不会建立,也不会瓦解。”

Chinese and Russian elites consider democracy promotion an existential threat.

中俄精英认为民主推广是对其生存的威胁。

Moreover, once ideological differences entered the equation, it became hard to talk about anything else, in part because debates over ideology could imply calls for regime change. In 1971, after a relatively productive conversation with two Soviet diplomats, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai exploded when one of them raised the issue of a People’s Daily article that they believed called for the Soviet people to start a revolution. Zhou noted that the Soviet Union was hosting Wang Ming, an early CCP leader who had clashed with Mao and been effectively exiled. “You think that we fear him,” Zhou said. “He is worse than shit!” When one Soviet diplomat asked a Chinese participant to stop yelling, saying “a shout is not an argument,” the Chinese diplomat fired back: “If not for shouting, you will not listen.”

此外,一旦意识形态分歧进入讨论范围,就很难再谈其他事情,部分原因是关于意识形态的辩论可能暗示对政权更迭的呼吁。1971年,在与两名苏联外交官进行相对富有成效的对话后,中国总理周恩来在其中一人提到《人民日报》的一篇文章时勃然大怒,他们认为该文章呼吁苏联人民发动革命。周指出,苏联正在接待早期中共领导人王明,王曾与毛发生冲突并被有效流放。“你们以为我们怕他,”周说,“他比屎还糟!”当一名苏联外交官要求一名中国参与者停止喊叫,说“喊叫不是争论”时,中国外交官回击道:“如果不喊,你们就不会听。”

Today’s Russia, however, is distant from the ideals of communism, to put it mildly. Although Putin once called the collapse of the Soviet Union a “geopolitical catastrophe,” he has often revealed rather negative views of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In his speech on the eve of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, he blamed Lenin for creating modern Ukraine and spoke of Stalin’s “dictatorship” and “totalitarian regime.” Xi Jinping, on the other hand, continues to take communism’s legacy seriously. According to an Australian diplomat, Russian diplomats found it odd when, on one occasion, Xi quoted to them the Russian revolutionary novel How the Steel Was Tempered. Although not a dogmatist, Xi cares deeply about ideology and has even blamed the collapse of the Soviet Union in part on Moscow’s failure to ensure that people took Marxism-Leninism seriously.

然而,今天的俄罗斯,与共产主义理想相去甚远。尽管普京曾称苏联解体是“地缘政治灾难”,但他经常透露对苏联共产党的负面看法。在俄罗斯入侵乌克兰前夕的演讲中,他指责列宁创造了现代乌克兰,并谈到斯大林的“独裁”和“极权政权”。另一方面,习近平继续认真对待共产主义遗产。根据一位澳大利亚外交官的说法,俄罗斯外交官发现,当习近平曾向他们引用俄国革命小说《钢铁是怎样炼成的》时,这很奇怪。虽然不是教条主义者,习近平非常重视意识形态,甚至将苏联解体部分归咎于莫斯科未能确保人们认真对待马克思列宁主义。

Despite these important differences, Chinese and Russian elites do share a conservative, statist worldview. They both see attacks on their history as Western plots to delegitimize their regimes and consider democracy promotion an existential threat. They both appreciate traditional values as a bulwark against instability and think the West is tearing itself apart with cultural debates. They both have concluded that authoritarian regimes are better at dealing with modern challenges. They both want their countries to regain a lost status and lost territory. Putin and Xi even spin the same legitimation narrative, claiming their predecessors allowed an intolerable (and Western-influenced) degradation of authority that only their strongman rule could arrest.

尽管存在这些重要差异,但中俄精英确实分享了一种保守的、国家主义的世界观。他们都认为对其历史的攻击是西方的阴谋,旨在使其政权失去合法性,并认为民主推广是对其生存的威胁。他们都欣赏传统价值观,认为这是对抗不稳定的堡垒,认为西方正在因文化辩论而自我撕裂。他们都认为威权政权更善于应对现代挑战。他们都希望自己的国家重新获得失去的地位和领土。普京和习近平甚至用相同的合法化叙述,声称他们的前任允许权威的不可容忍的(和西方影响的)退化,只有他们的强人统治才能阻止这种退化。

MAN TO MAN 人对人

Another factor binding Moscow and Beijing today are the warm relations between Putin and Xi. Chinese and Russian media tout a strong personal relationship between the two leaders, although it is hard to say how genuine the supposed friendship is. Putin was trained as a KGB agent, an experience that taught him how to manage people, and Xi would have learned similar tricks from his father, a master of the party’s “united front” efforts to win over skeptics. Putin and Xi are very different people. Putin once broke his arm fighting toughs on the Leningrad subway. Xi has consistently demonstrated extraordinary self-control, as evidenced by his ability to rise to power without anyone knowing what he really thought. Putin enjoys high living, while Xi’s personal style seems to border on ascetic. But at the very least, a functional relationship between Russian and Chinese leaders is something of a historical anomaly.

今天,普京和习近平之间的温暖关系是将莫斯科和北京联系在一起的另一个因素。中俄媒体都宣称两位领导人之间有着牢固的个人关系,尽管这种所谓的友谊有多真诚还很难说。普京曾接受过作为克格勃特工的训练,这段经历教会了他如何管理人际关系,而习近平则可能从他的父亲那里学到类似的技巧,习仲勋是党内“统一战线”努力争取怀疑者的高手。普京和习近平是非常不同的人。普京曾在列宁格勒地铁上与恶棍打斗时折断了手臂,而习近平则始终表现出非凡的自我控制力,这从他在上台前没有人知道他真正想法的能力中可见一斑。普京喜欢奢华的生活,而习近平的个人风格似乎接近于苦行僧。但至少,中俄领导人之间的功能性关系在历史上是一种异常现象。

For Mao, Stalin’s ideological credentials and contributions to Soviet history made him a titan of the communist world. Yet Stalin’s cautious attitude toward the Chinese Revolution in the second half of the 1940s rankled him. So did Stalin’s high-handedness during the negotiations for the alliance treaty between the two countries in 1949 and 1950. After Stalin’s death, Mao felt his own stature far outweighed Khrushchev’s, and the chairman famously treated his Soviet counterpart with disdain.

对毛泽东来说,斯大林的意识形态资历和对苏联历史的贡献使他成为共产主义世界的巨人。然而,斯大林在1940年代后半期对中国革命的谨慎态度让毛泽东感到恼火。斯大林在两国之间联盟条约谈判中的高压态度也让他不满。斯大林死后,毛觉得自己的地位远远超过了赫鲁晓夫,毛以蔑视的态度对待他的苏联对手。

Mao was impressed by the toughness his protégé Deng Xiaoping displayed during interminable debates over ideology in Moscow in the 1960s, when Deng was Beijing’s most prominent attack dog on the world stage. After Mao’s death, Deng noted that countries close to the Soviet Union had dysfunctional economies, while U.S. allies thrived. By the time Deng became China’s paramount leader, many of his associates hoped for a better relationship with Moscow, but Deng ignored those voices. He and Gorbachev met only once—during the Tiananmen Square protests—and Deng concluded that the Soviet leader was “an idiot.” After the Soviet Union collapsed and Boris Yeltsin became president of Russia, the Chinese were at first skeptical of him, given his role in helping bring about the demise of communism, but relations among top leaders gradually improved. Deng’s successor, Jiang Zemin, had studied in the Soviet Union and could sing old Sino-Soviet friendship songs.

毛对他的门徒邓小平在1960年代莫斯科漫长的意识形态辩论中表现出的强硬态度印象深刻,当时邓是北京在世界舞台上最突出的攻击者。毛死后,邓指出,靠近苏联的国家经济失调,而美国的盟友则繁荣。到邓成为中国最高领导人时,他的许多同事希望与莫斯科建立更好的关系,但邓无视这些声音。他和戈尔巴乔夫只会面过一次——在天安门广场抗议期间——邓认为这位苏联领导人是“白痴”。苏联解体后,鲍里斯·叶利钦成为俄罗斯总统,中国人起初对他持怀疑态度,因为他在促成共产主义垮台中扮演了重要角色,但顶级领导人之间的关系逐渐改善。邓的继任者江泽民曾在苏联学习,能够唱老的中苏友谊歌曲。

Warm interpersonal relations are not the main reason Russia and China are so close today, but the past certainly shows how much individual leaders can matter when they have disdain for their counterparts and the countries they lead. And despite their differences, it is not hard to guess why Putin and Xi might get along on a personal level. They are almost the same age, and they are both sons of men who sacrificed for their countries. And perhaps most important, they both had formative experiences about the dangers of political instability. During the Cultural Revolution, Xi and his family were kidnapped and beaten by Mao’s Red Guards, and in 1989, Putin, then a KGB officer stationed in Dresden, watched as East Germany collapsed around him while he could not get guidance from Moscow. The two have much to talk about when they make blini and dumplings together for the television cameras.

温暖的个人关系并不是今天中俄关系如此紧密的主要原因,但过去确实表明,当领导人蔑视他们的对手及其领导的国家时,会产生多么大的影响。尽管存在差异,但不难猜测为什么普京和习近平可能在个人层面上相处得很好。他们几乎是同龄人,都是为国家牺牲的父亲的儿子。也许最重要的是,他们都在政治不稳定的危险中形成了重要的经验。文革期间,习近平和他的家人被毛的红卫兵绑架和殴打;1989年,普京作为驻德累斯顿的克格勃军官,目睹了东德的崩溃,而无法从莫斯科获得指导。他们在一起为电视摄像头做煎饼和饺子时,有很多话题可聊。

TEAMING UP 合作共赢

Greater flexibility in the partnership between Beijing and Moscow today also makes it hardier than it was in the past. Since 1949, the central strategic challenge has been how the two powers, which together make up Eurasia’s authoritarian heartland, can cooperate effectively against the threat of the U.S.-led democratic periphery. Despite the extraordinary strength of Washington’s position in their neighborhoods, Beijing and Moscow have struggled to get this coordination right. Time and time again, they have proved unwilling to sacrifice their interests for each other, driven in part by a suspicion that the other is selling them out and seeking improved relations with the West.

今天北京和莫斯科之间更大的灵活性使得这种伙伴关系比过去更持久。自1949年以来,中央战略挑战一直是如何有效合作对抗由美国主导的民主外围所带来的威胁,尽管华盛顿在他们邻国中的地位异常强大,北京和莫斯科在协调这一点上屡屡受挫。他们一次次证明不愿为彼此牺牲自己的利益,部分原因是怀疑对方在出卖自己并寻求与西方改善关系。

Before the Sino-Soviet split, the alliance between Moscow and Beijing created real problems for the United States real benefits for the two powers. A calm border between the two countries allowed them to focus on confronting the West and to share military technology. In 1958, when China attacked Taiwan in an attempt to take control of the island, Khrushchev came to Beijing’s aid by publicly warning that he would intervene to protect China if the United States entered the conflict—even though he resented that Beijing had failed to tell him about its plans ahead of time.

在中苏分裂之前,莫斯科和北京之间的联盟给美国带来了真正的问题,并为这两个大国带来了真正的好处。两国之间平静的边界让他们可以专注于对抗西方,并分享军事技术。1958年,中国试图控制台湾岛时,赫鲁晓夫通过公开警告如果美国介入冲突,他将干预保护中国来援助北京,尽管他对北京没有提前告知计划感到不满。

Yet the heartland’s relationship with the periphery has always been a mix of coexistence and competition, and Moscow and Beijing have rarely given equal weight to those dueling objectives. During the 1950s and 1960s, China was essentially shut out of the international system while the Soviet Union was largely a status quo power. Mao’s cavalier language threatening nuclear war, along with his use of force on the Chinese-Indian border and against the offshore islands in the Taiwan Strait, raised fears in the Kremlin that China would drag the Soviet Union into war. Moscow supported the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, declined to help China during various crises, and hoped for détente with the West—moves that led leaders in Beijing to conclude that Moscow cared more about the West than it did about the communist bloc.

然而,心脏地带与外围的关系一直是共存与竞争的混合体,莫斯科和北京很少对这些相互冲突的目标给予同等重视。在1950年代和1960年代,中国实际上被国际体系排斥在外,而苏联基本上是一个现状大国。毛的核战争威胁性语言,以及他在中印边境和台湾海峡对近海岛屿使用武力,令克里姆林宫担心中国会将苏联拖入战争。莫斯科支持《核不扩散条约》,在各种危机期间拒绝帮助中国,并希望与西方缓和——这些举动让北京领导人认为莫斯科更关心西方而非共产主义阵营。

Now, China and Russia have switched positions. Beijing hopes to benefit economically and technologically from continued ties with the United States and Europe, while Moscow sees itself in a purely competitive relationship. The Russians undoubtedly wish that Beijing would provide lethal aid in Ukraine and agree to the Power of Siberia 2, a proposed pipeline that would send natural gas to northeastern China. Unlike during the heyday of the Sino-Soviet alliance, however, Beijing is not technically beholden to sacrifice its economic or reputational interests for Moscow because the two are not formal allies. The Russians have less reason to feel betrayed—and the Chinese have less reason to fear entrapment.

现在,中国和俄罗斯交换了立场。北京希望从与美国和欧洲的持续联系中在经济和技术上受益,而莫斯科则将自己视为纯粹的竞争对手。毫无疑问,俄罗斯希望北京在乌克兰提供致命援助,并同意“西伯利亚力量2号”输送天然气到中国东北的拟议管道。然而,不像中苏联盟鼎盛时期,北京在技术上没有义务为了莫斯科牺牲其经济或声誉利益,因为两国并非正式盟友。俄罗斯人感觉到被背叛的理由更少——而中国人对被套牢的恐惧也更少。

HISTORY LESSONS 历史教训

As the son of a man so involved in his country’s relationship with Moscow, Xi Jinping knows his history. The past has shown the dangers of both incautious embrace and full-blown enmity. Now, Xi wants to have his cake and eat it, too—move close enough to Russia to create problems for the West, but not so close that China has to decouple entirely. It is not an easy cake to bake, and it may become harder. Washington is trying to make it as difficult as possible by painting Russia and China with the same brush, portraying China (correctly) as facilitating Russia’s war in Ukraine. The conflict has created real economic and reputational costs for Beijing, even as it shies away from some of Moscow’s requests.

作为一位深谙中苏关系的人的儿子,习近平知道这段历史。过去显示了不谨慎的亲近和完全敌对的危险。现在,习近平希望既要接近俄罗斯以给西方制造问题,但又不至于让中国完全脱钩。这不是一块易做的蛋糕,而且可能变得更难。华盛顿正试图使之尽可能困难,通过把俄罗斯和中国同样描绘,将中国(正确地)描绘成帮助俄罗斯在乌克兰的战争。这场冲突给北京带来了实际的经济和声誉成本,尽管它避开了莫斯科的一些要求。

Problems exist in any relationship, especially between great powers. What is different from the Cold War is that thorny ideological and personal issues no longer make such challenges so hard to manage. Absent high-impact but low-probability events—such as the use of a nuclear weapon in Ukraine, the collapse of the Russian state, or a war over Taiwan—China will probably maneuver within the broad parameters it has already set out for the relationship. Sometimes Beijing will suggest a close relationship with Moscow, and sometimes it will imply a more distant one, modulating its message as the situation demands. The United States, for its part, may be able to shape some of China’s calculus and limit what kinds of help Russia receives. For the foreseeable future, however, Xi’s model for Chinese-Russian relations will likely prove sturdier than in the past because, perhaps counterintuitively, it avoids the danger of intimacy.

任何关系中都会存在问题,特别是在大国之间。与冷战不同的是,意识形态和个人问题不再使这些挑战难以管理。除非出现高影响但低概率的事件——如在乌克兰使用核武器、俄罗斯国家的崩溃或台湾战争——中国可能会在已为这种关系设定的广泛参数内运作。有时北京会暗示与莫斯科的密切关系,有时则会暗示更疏远的关系,随着形势需要调整其信息。美国方面,可能能够影响中国的一些考量,限制俄罗斯所能获得的帮助类型。然而在可预见的未来,习近平的中俄关系模式可能比过去更坚固,因为或许出人意料的是,它避免了亲密的危险。